Deep Cleaning Explained: Essential for Healthy Gums in Miami

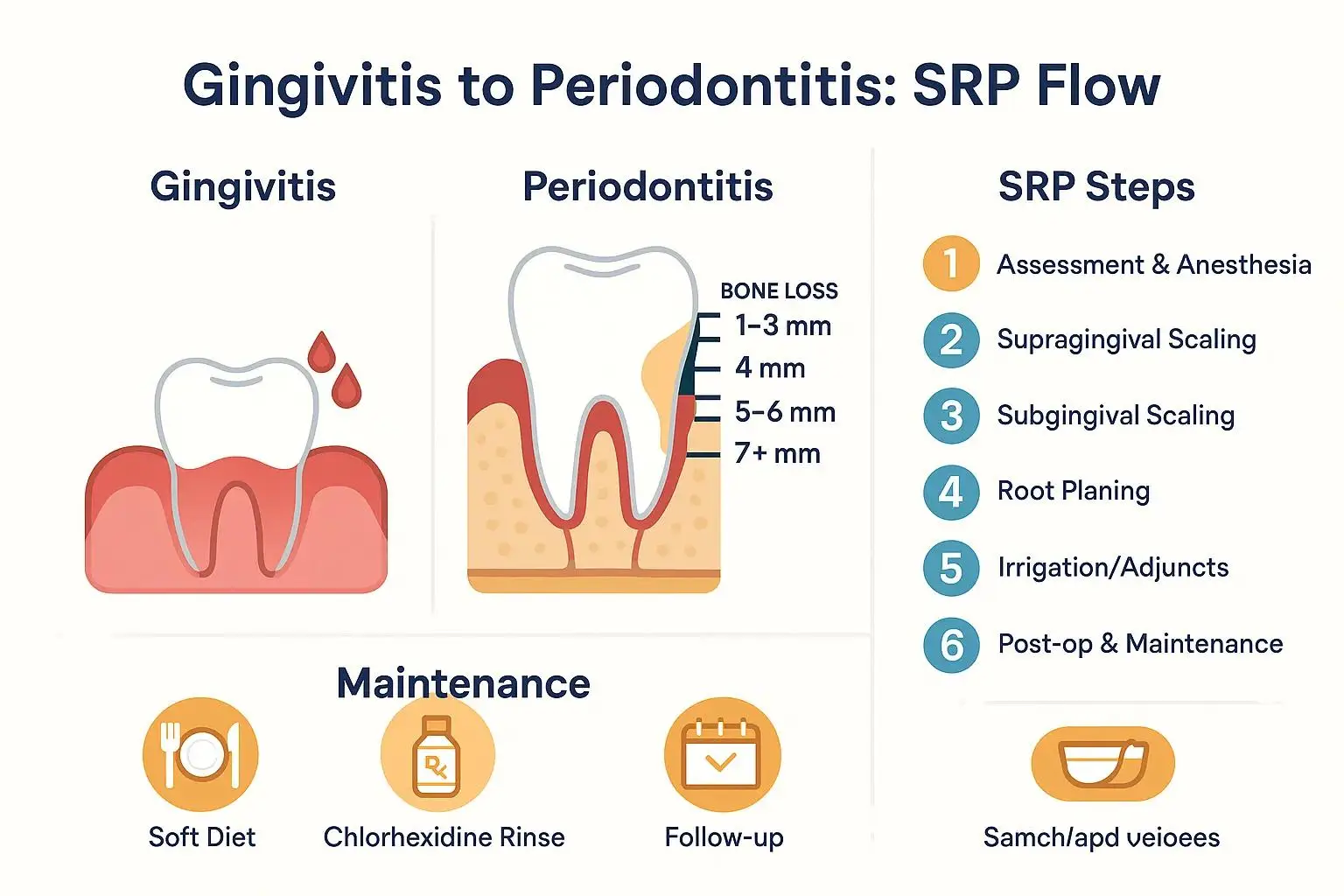

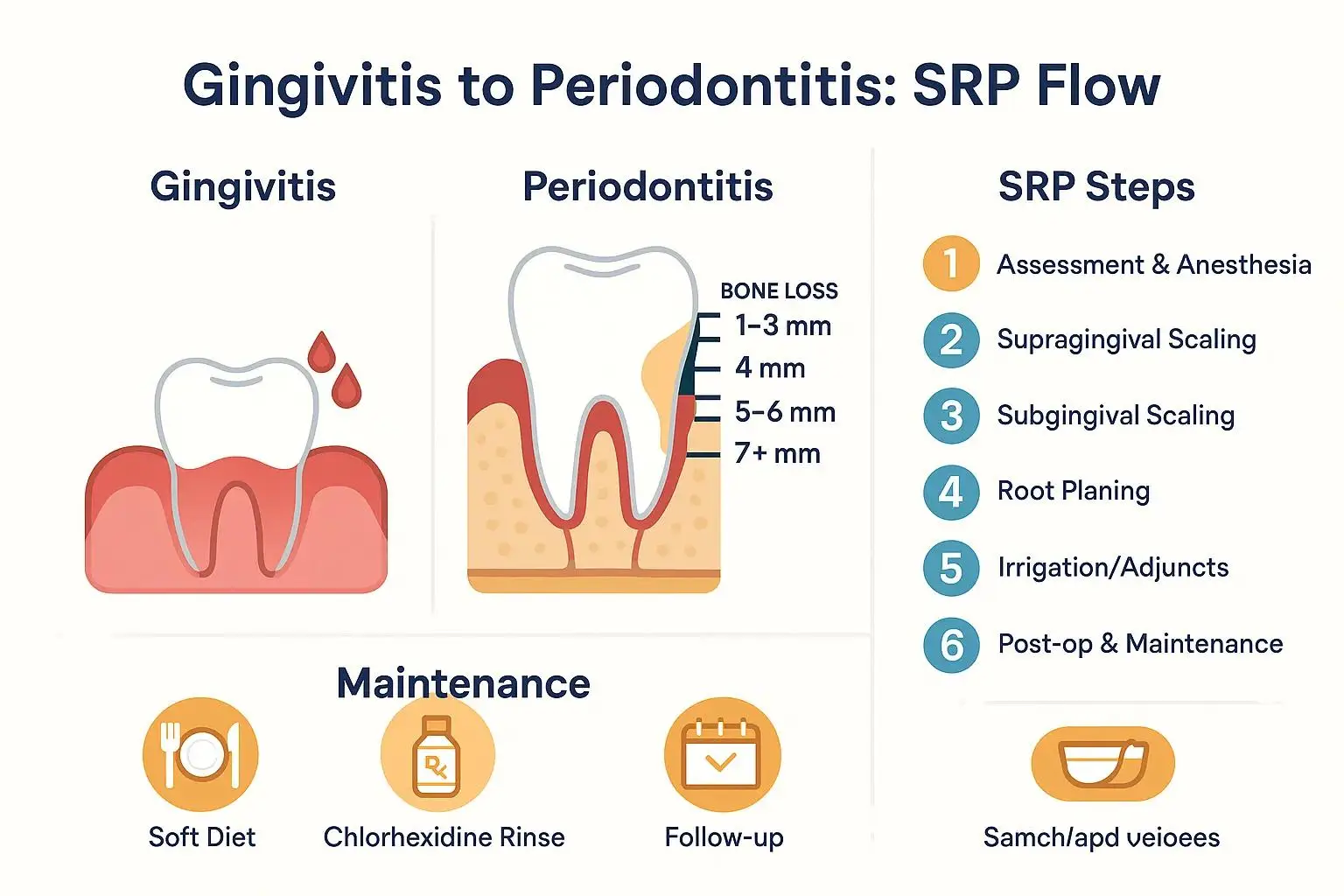

Understanding Gingivitis & Periodontis

Gum disease ranges from reversible surface inflammation to destructive, bone-affecting periodontal disease, and understanding the differences is the first step toward preserving teeth and overall health. This guide explains what gingivitis and periodontitis are, how clinicians diagnose disease, the clinical thresholds that indicate a deep cleaning (scaling and root planing), and what patients can expect during treatment and recovery. Many people notice bleeding, bad breath, or gum recession and wonder whether those signs are temporary or a signal of progressive disease; this article shows how simple examinations like probing and radiographs reveal the underlying condition and drive treatment decisions. You will learn the stages and symptoms of periodontal disease, objective pocket-depth thresholds, a step-by-step description of scaling and root planing, post-procedure pain management, and practical prevention strategies to keep your gums healthy. Throughout, the content integrates semantic clinical markers such as plaque, tartar, pocket depth, and bone loss, and gives actionable checklists so you can recognize when to seek care. By the end you will understand when non-surgical therapy is appropriate, how it works biologically to reduce inflammation, and how routine maintenance prevents relapse.

What Is Gingivitis and How Does It Differ from Periodontal Disease?

Gingivitis is inflammation confined to the gum tissue caused primarily by plaque accumulation, while periodontal disease (periodontitis) occurs when that inflammatory process extends into deeper structures causing connective tissue destruction and alveolar bone loss. The mechanism begins with plaque—a biofilm of bacteria—adhering to enamel and gingival margins, which provokes an immune response and visible redness, bleeding, and swelling; when plaque calcifies into tartar and migrates below the gumline, bacterial toxins and host response drive pocket formation. Early detection of gingivitis matters because it is usually reversible with improved hygiene and professional cleaning, whereas periodontitis creates pocket depths that harbor bacteria and may be only partially reversible with non-surgical care. Understanding this continuum helps patients and clinicians select conservative treatments early to prevent structural loss and preserve oral-systemic health outcomes.

What Are the Early Signs and Symptoms of Gingivitis?

Gingivitis typically presents with bleeding on brushing or flossing, red or swollen gums, tenderness to touch, and persistent halitosis (bad breath), all of which reflect superficial inflammation of the gingival tissues. Patients often report noticing blood on a toothbrush or floss, gums that look puffy or darker than usual, or a metallic taste after eating; these symptoms indicate that plaque control is insufficient and professional intervention is advisable. Identifying these early signs allows prompt reversal through focused home care and a professional prophylaxis, which reduces bacterial load and resolves inflammation. The next section explains how unchecked gingivitis can progress to deeper periodontal involvement when calculus and subgingival biofilm persist.

- Common early signs of gingivitis include bleeding, swelling, tenderness, and halitosis.

- These symptoms are reversible with targeted hygiene and professional cleaning.

- Persistent symptoms despite home care signal the need for periodontal evaluation.

This list highlights patient-visible cues that should prompt discussion with a dental professional and leads into how persistent inflammation advances to periodontitis.

How Does Gingivitis Progress to Periodontal Disease?

The pathological progression from gingivitis to periodontitis follows a sequence: plaque biofilm accumulates, minerals in saliva cause calculus formation, bacteria colonize subgingival pockets, and the host immune response damages connective tissue and alveolar bone. As pockets deepen they trap more bacteria and anaerobic species thrive, producing enzymes and toxins that break down collagen and bone, so probing depths and radiographic bone loss become objective markers of progression. Systemic factors such as smoking, poor glycemic control, and certain medications accelerate this process by impairing host defenses and tissue repair, increasing the likelihood that gingival inflammation will evolve into destructive periodontitis. Recognizing and interrupting this cascade early preserves attachment and avoids more invasive surgical interventions.

What Are the Stages and Symptoms of Periodontal Disease?

Periodontal disease is classified by clinical stage—ranging from gingivitis through early (mild) periodontitis to moderate and advanced disease—each stage defined by pocket depth, attachment loss, and radiographic bone loss. Clinicians use periodontal probing, charting, and radiographs to determine stage, which guides whether non-surgical therapy, adjunctive antimicrobials, or surgical management is indicated. Symptoms escalate from reversible gingival bleeding and halitosis to gum recession, tooth mobility, and eventual tooth loss as bone support diminishes; systemic implications such as heightened inflammatory burden can also influence overall health. Understanding stage-based signs enables patients to see why a deep cleaning is recommended for some cases and why maintenance is essential after therapy.

The table below summarizes common stage markers and typical clinical approaches so patients can quickly compare presentation and likely treatments.

How Is Periodontal Disease Diagnosed and What Are Its Key Symptoms?

Periodontal diagnosis combines a clinical periodontal exam—probing depths, bleeding on probing, mobility assessment—and radiographs that reveal bone levels; these objective measures define disease severity and prognosis. Key patient symptoms that commonly accompany clinical findings include gum recession, chronic halitosis, food packing, and increasingly loose teeth, which often prompt referral to a periodontist when non-surgical measures fail. Dentists also evaluate risk factors such as smoking and diabetes that modify both disease trajectory and treatment planning, integrating the overall health picture into care decisions. A clear diagnosis informs whether scaling and root planing will likely succeed or whether adjunctive or surgical therapy should be considered.

What Are the Risks and Consequences of Untreated Periodontal Disease?

Untreated periodontitis progressively destroys the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone, causing tooth mobility, drifting, and eventual tooth loss, which increases restorative needs and long-term costs. Beyond localized effects, chronic periodontal inflammation contributes to systemic inflammatory burden and has been associated with poorer glycemic control in diabetes and potential cardiovascular risks, underscoring the mouth–body connection. Delaying treatment can convert a treatable condition into one requiring surgery or prosthetic replacement with greater patient morbidity. Early detection, therefore, is both a dental and systemic health priority to limit irreversible tissue destruction.

When Is a Deep Cleaning Required for Gum Disease?

A deep cleaning, commonly called scaling and root planing (SRP), is indicated when clinical examination shows persistent periodontal pockets (typically ≥4 mm), bleeding on probing, and subgingival calculus that cannot be removed by routine prophylaxis. The clinical decision also integrates radiographic evidence of bone loss, tooth mobility, and the patient’s risk profile—such as smoking or poorly controlled diabetes—that increases disease progression; when these indicators coexist, SRP aims to remove biofilm and calculus below the gumline and allow reattachment. Not every pocket requires SRP; shallow sites managed with improved hygiene may resolve without it, but pockets of 4 mm or greater that bleed and retain calculus are common SRP candidates. The following comparison table outlines objective indicators clinicians weigh when recommending deep cleaning versus alternative approaches.

What Are the Signs That Indicate You Need a Deep Cleaning?

Patients should consider evaluation for deep cleaning if they notice persistent bleeding during brushing or flossing, ongoing bad breath despite hygiene efforts, gum swelling, or tooth sensitivity and mobility. Clinically, indicators include pockets ≥4 mm on probing, visible subgingival calculus on radiographs or exam, and sites that fail to respond after an initial hygiene phase. Non-resolution after a professional prophylaxis and improved home care is a red flag that deeper subgingival debridement may be necessary to arrest disease. If these signs are present, prompt assessment helps determine whether SRP can restore periodontal health and prevent progression.

- Persistent bleeding during brushing or flossing

- Chronic halitosis that doesn’t improve with brushing

- Pocket depths ≥4 mm or radiographic evidence of bone loss

This bullet list gives clear patient cues that should lead to scheduling a periodontal evaluation for possible deep cleaning.

How Does Gum Pocket Depth Affect the Need for Deep Cleaning?

Gum pocket depth is a numeric expression of attachment loss and is central to treatment planning: 1–3 mm is considered healthy, 4 mm often requires close monitoring or SRP, 5–6 mm usually benefits from SRP with possible adjuncts, and ≥7 mm may need surgical access if non-surgical therapy fails. Deeper pockets harbor anaerobic bacteria and calculus that are physically difficult to remove without careful subgingival instrumentation, so reducing pocket depth through SRP improves oral hygiene access and reduces inflammation. Prognosis improves when pockets are reduced and maintained with periodontal maintenance appointments, which prevent recolonization and recurring pocket deepening. Regular re-evaluation after SRP determines whether additional therapy or referral is necessary based on pocket reduction and tissue response.

People First Dentistry and Dr. Omar Villavicencio approach these assessments with a focus on early detection and clear patient education, ensuring each evaluation includes probing, risk assessment, and a personalized plan. The practice emphasizes gentle dentistry and hour-long initial visits for new patients so clinicians can explain the implications of pocket depths and outline achievable goals for reversing disease. This patient-centered evaluation supports shared decision-making and helps patients understand when SRP is the right step versus when conservative monitoring is appropriate. Such an approach prioritizes preserving natural dentition while aligning treatment with the patient’s overall health.

What Does the Deep Cleaning Procedure Involve and How Does It Help?

Scaling and root planing is a methodical, non-surgical procedure that removes plaque and tartar from above and below the gumline and smooths root surfaces to promote tissue reattachment and reduce bacterial reservoirs. Mechanistically, removing calculus eliminates a niche for pathogenic biofilms and smoothing roots decreases surface roughness where bacteria cling, allowing gingival tissues to re-adapt and inflammation to subside. SRP commonly uses a combination of ultrasonic scalers and hand instruments under local anesthesia to maximize comfort while achieving thorough debridement; adjunctive therapies such as localized antimicrobials or antiseptic rinses may be used when indicated. Successful SRP reduces pocket depths, decreases bleeding, improves halitosis, and lowers systemic inflammatory markers linked to periodontal infection.

What Are the Steps of the Scaling and Root Planing Procedure?

The procedure typically follows these numbered steps to ensure patient understanding and predictable outcomes:

- Assessment and anesthesia: The clinician charts pockets and applies local anesthesia to control discomfort.

- Supragingival scaling: Plaque and calculus above the gumline are removed to improve access.

- Subgingival scaling: Ultrasonic and hand scalers remove calculus and biofilm from pocket depths.

- Root planing: Root surfaces are smoothed to remove toxins and encourage reattachment.

- Irrigation and adjuncts: Antiseptic rinses or local antimicrobials may be placed if needed.

- Post-op instructions and maintenance planning: Patients receive aftercare guidance and a PM schedule.

Patients often feel pressure and vibration rather than pain during SRP due to anesthesia, and clinicians typically space treatment quadrant-by-quadrant to maximize comfort and effectiveness. At People First Dentistry, clinicians combine gentle techniques with calming care, use modern ultrasonic devices to shorten instrumentation time, and allow thorough one-on-one visits so anxious patients receive focused attention and comfort measures. This practice-level emphasis on technology and patient comfort reduces procedural stress and supports better clinical outcomes.

What Are the Benefits of Deep Cleaning for Oral and Overall Health?

Deep cleaning confers multiple oral benefits including reduced pocket depths, decreased bleeding, improved breath, and stabilization of tooth mobility by arresting the destructive bacterial process. Biologically, SRP reduces bacterial load and local inflammation, creating conditions conducive to reattachment and bone preservation when applied early enough in the disease course. There is also evidence that effective periodontal therapy can lower systemic inflammatory markers, which may positively influence conditions like diabetes; while associations to systemic disease are complex, reducing oral inflammation contributes to overall health management. Regular periodontal maintenance following SRP extends these benefits by preventing recolonization and monitoring any residual disease activity.

- Reduced pocket depth improves hygiene access and long-term prognosis.

- Less bleeding and inflammation enhance patient comfort and appearance.

- Potential systemic benefits include lower inflammatory burden and improved metabolic control.

This benefits list summarizes why SRP is a cornerstone of non-surgical periodontal therapy and leads into recovery expectations addressed next.

How Can Pain and Recovery Be Managed After a Deep Cleaning?

After scaling and root planing, most patients experience modest discomfort, sensitivity, and mild swelling that peak within the first 48–72 hours and subside over one to two weeks as tissues heal. Pain management typically involves local anesthesia during the procedure to prevent intraoperative pain and short-term analgesics—often over-the-counter anti-inflammatories—for post-op discomfort; topical gels and prescribed chlorhexidine rinses may reduce irritation and microbial load. Clinicians advise a soft-food diet, gentle oral hygiene near treated sites, and avoidance of tobacco to support healing and prevent reinfection. Monitoring during periodontal maintenance visits helps detect any complications early and ensures tissue re-attachment progresses as expected.

The table below compares common pain management options, expected effects, and typical duration to help patients anticipate recovery and choose appropriate measures.

Is Deep Cleaning Painful and What Comfort Measures Are Available?

Deep cleaning is generally well tolerated because clinicians use local anesthesia to numb treated areas, limiting procedural pain; sensitivity and soreness after the appointment are common but manageable with analgesics. For patients with dental anxiety, options such as calming communication, noise-reducing headphones, and chairside comfort techniques reduce stress, while modern ultrasonic scalers minimize appointment length and vibration. Topical gels or desensitizing agents applied post-op help with surface sensitivity, and some practices offer scheduling flexibility to allow longer, unhurried visits for anxious patients. If pain persists beyond expected timelines or is severe, patients should contact their clinician to rule out infection or incomplete debridement.

What Is the Typical Recovery Time and Aftercare Following Deep Cleaning?

Immediate recovery usually involves 48–72 hours of the most noticeable discomfort, with gradual reduction in soreness and sensitivity over one to two weeks as gingival tissues begin re-attachment and inflammation subsides. Aftercare includes gentle brushing with a soft toothbrush, interdental cleaning as tolerated, saline rinses or prescribed chlorhexidine for short periods, and avoiding hard or crunchy foods that irritate treated sites. Follow-up appointments are scheduled to re-probe and measure pocket reduction; if pockets remain deep, further treatment or referral may be considered. Patients should expect a maintenance program—periodontal maintenance visits at individualized intervals—to preserve improvements and prevent recurrence.

How Can You Prevent Gum Disease and Maintain Healthy Gums?

Preventing gum disease combines effective home care, lifestyle measures, and routine professional maintenance to control plaque and minimize host risk factors for progression. Daily habits—twice-daily brushing with fluoride toothpaste, daily interdental cleaning (floss or interdental brushes), and appropriate use of antiseptic rinses when recommended—reduce biofilm buildup and lower the chance of calculus formation. Lifestyle changes such as smoking cessation and good glycemic control for people with diabetes decrease susceptibility and improve treatment outcomes when disease occurs. Regular dental checkups and tailored periodontal maintenance schedules maintain gains from therapy and enable early intervention if pockets reappear.

What Home Care Practices Help Prevent Gingivitis and Periodontal Disease?

Good home care focuses on mechanical disruption of plaque and includes proper brushing technique, daily interdental cleaning, and selective use of antimicrobial rinses to reduce microbial load between visits. Using a soft-bristled or electric toothbrush with gentle, angulated strokes removes plaque at the gingival margin, while interdental brushes or floss clean the contact zones where periodontal pathogens thrive; consistency is more important than occasional vigorous cleaning. Antimicrobial mouthrinses and short courses of prescription agents may be advised for high-risk sites, and patients should be taught effective technique during hygiene appointments. These daily practices form the foundation for preventing gingivitis and, by extension, periodontitis.

- Brush twice daily with a soft or electric toothbrush using gentle, angulated strokes.

- Clean between teeth once daily with floss or interdental brushes to remove interdental biofilm.

- Attend regular professional cleanings and follow any prescribed antiseptic regimens.

This practical checklist empowers patients to reduce plaque formation and sets the stage for when to seek professional care.

When Should You See a Dentist or Periodontist for Gum Health?

Seek professional evaluation if you notice persistent bleeding, increasing pocket depths, gum recession, chronic bad breath, or tooth mobility; early referral to a periodontist may be warranted for persistent or advanced disease. Routine intervals for periodontal maintenance depend on disease severity and response to therapy but commonly range from three to six months after active treatment to prevent recurrence. General dentists manage early disease and perform SRP, while a periodontist is consulted for complex cases, surgical interventions, or when regenerative therapies are considered. Timely professional involvement preserves teeth, optimizes outcomes, and links oral care with broader systemic health management.

People First Dentistry offers preventive services such as personalized hygiene instruction, individualized maintenance intervals, and patient education delivered in a stress-free environment focused on gentle dentistry and whole-person health. Dr. Omar Villavicencio leads a patient-centered approach that emphasizes extended initial visits for comprehensive assessment and tailored prevention plans, helping patients stay on top of gum health with clear next steps. If you are noticing symptoms or have risk factors, scheduling an evaluation with clinicians who prioritize patient comfort and clear communication is an effective step toward long-term gum health and reduced systemic inflammation.